By Tom Lancaster

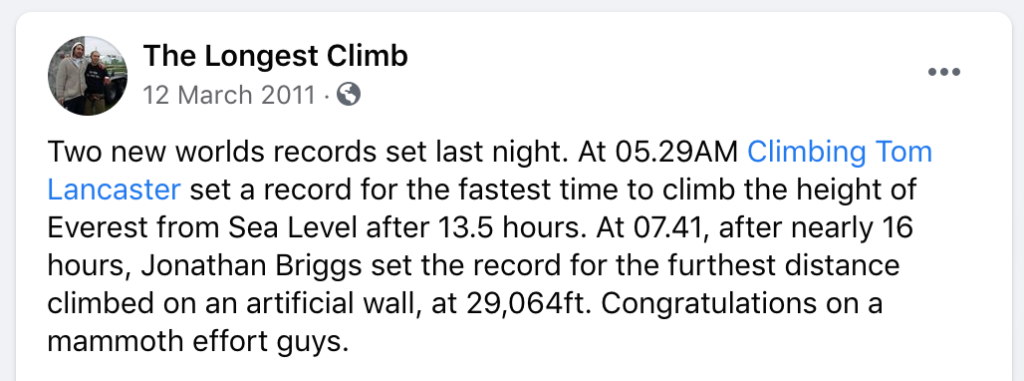

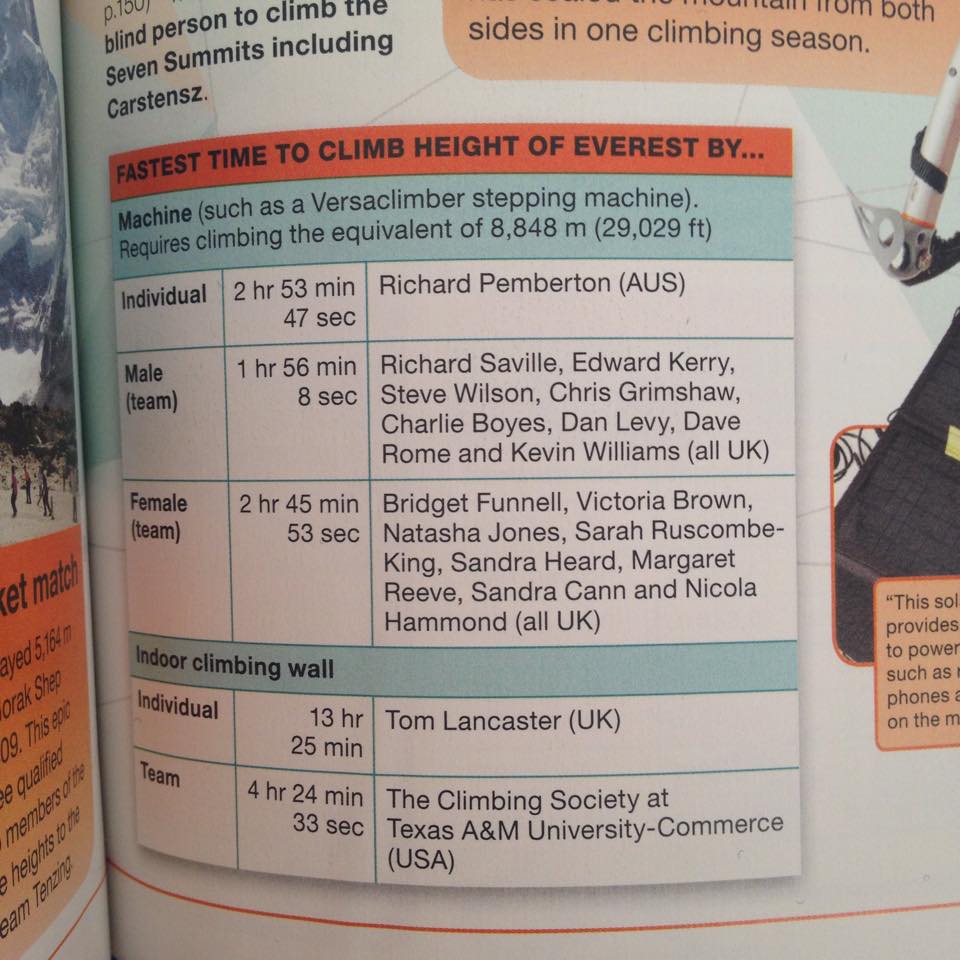

I raised over £7000 for three charities. I did something that had never been done by an individual before. It was an incredible accomplishment.

But the only way this happened was simply taking the next step every day. Getting up every time I fell down. One foot in front of the other, over and over again.

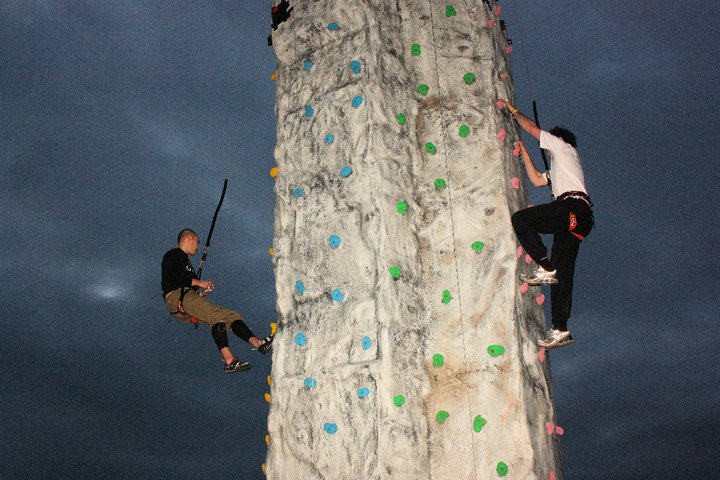

Even though those last 104 climbs were among the most miserable physical experiences of my life, it didn’t feel like a huge thing. I did it in half the time we had predicted, even with a 2 hour break in the middle.

Even though the whole ordeal was brutally hard, It wasn’t nearly as hard as I thought it would be.

When Johnny and I started out, we had no idea how to train, what to eat, or even if this lunatic idea was even possible. Through the whole process, life continued to happen. Jobs, relationships, family drama all happening outside of the sphere of The Longest Climb. We kept taking what seemed to be the next step.

Sometimes we fucked it up. One of us would train too hard and injure ourselves. Something got posted on the blog that didn’t go down well. We fought between the two of us. A lot.

But each time we got knocked down, we dusted ourselves off, adjusted the plan based on the new data, and put one foot in front of the other again.

The same is true for that thing you want to do. You have this picture in your head of how hard it will be. How incapable you are. All the reasons why it will fail.

But the only guarantee of failure is never starting.